Artigo

| Antioxidant potential, photoprotective activity, and HPLC-ESI-MS profiling of Evolvulus species from the Brazilian Caatinga |

|

Maria Beatriz Félix Mendes NunesI; Thalisson Amorim de SouzaI; Juliana de Medeiros GomesI; Carlos Vinicius Azevedo da SilvaII; Laiane Caline Oliveira PereiraI; José Iranildo Miranda de MeloIII; Hector Henrique Ferreira KoolenII I. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Produtos Naturais e Sintéticos Bioativos, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 58051-900 João Pessoa - PB, Brasil Received: 07/06/2025 *e-mail: josean@ltf.ufpb.br Editor handled this article: Jorge M. David Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is a public health issue, especially in tropical and subtropical regions, where intense solar exposure contributes to a higher incidence of skin cancer. The growing concerns surrounding synthetic UV filters have prompted the search for natural and sustainable alternatives. The Brazilian semi-arid region represents a unique ecosystem whose flora harbors bioactive metabolites that exhibit remarkable potential for pharmaceutical and cosmetic innovation. This study investigated the chemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and photoprotective properties of two Evolvulus species (Convolvulaceae Juss.) native to this biome: E. frankenioides and E. glomeratus. Total phenolic and flavonoid contents were quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu and aluminum chloride methods, while antioxidant activity was evaluated using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assays, and the sun protection factor (SPF) was determined using the Mansur method. E. glomeratus exhibited higher phenolic content (172.61 mg GAE g-1), stronger antioxidant activity, and superior SPF (13.89) compared to E. frankenioides. Both extracts exceeded the minimum SPF threshold required by regulatory agencies. High-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS) analysis identified 19 phenolic compounds, mainly flavonoids and chlorogenic acids, which likely account for these effects. Overall, the results highlight the potential of E. glomeratus as a promising source for the development of natural, effective, and environmentally sustainable photoprotective formulations. INTRODUCTION The sun emits different types of radiation that reach Earth's surface, according to their frequency and wavelength, they are classified as ultraviolet (UV), visible, and infrared. The UV is subdivided into UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C, which are relevant to vitamin D synthesis.1 However, excessive exposure can damage the skin. UV-A induces tanning but also DNA mutations, contributing to cancer, while UV-B causes burns, pigmentation disorders, and skin cancer. The need for UV protection has driven the growing use of sunscreens, particularly in countries such as Brazil, where skin cancer incidence is rising.2,3 The widespread use of chemical sunscreens, including cinnamates and benzophenone derivatives, has raised environmental and health concerns. Synthetic UV filters disperse into aquatic systems, accumulate in organisms, and impair endocrine regulation and reproduction. In humans, some compounds trigger allergic reactions.4,5 Consequently, interest has increased in natural UV filters from plant extracts, which combine antioxidant and photoprotective properties with greater safety and sustainability.6,7 The Brazilian semi-arid region, marked by high solar incidence and low rainfall, hosts extensive plant biodiversity adapted to these harsh conditions. Evolvulus species (Convolvulaceae) are frequent in the Caatinga biome.8 E. alsinoides and E. nummularius have traditional uses in Africa and East Asia as anxiolytics and antioxidants.9,10 Studies further highlight this genus as a source of phenolic compounds with photoprotective potential.11 However, the literature remains scarce about Evolvulus phytochemical and biological potential, especially regarding its Brazilian representatives. In this context, two species stand out in the Brazilian semi-arid region: E. glomeratus (known as "melhoral"), used in folk medicine as an antipyretic,12 and E. frankenioides, valued as an ornamental plant.13 Neither has been chemically or pharmacologically characterized. Therefore, considering the environmental risks of synthetic UV filters and the bioactive potential of native plants, this study aims to evaluate the photoprotective and antioxidant activities of E. glomeratus and E. frankenioides. Furthermore, it seeks to identify and characterize their main secondary metabolites using high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection and electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn).

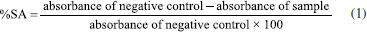

EXPERIMENTAL Plant material and extraction conditions The botanical material, consisting of aerial parts of Evolvulus frankenioides Moric. and Evolvulus glomeratus Nees & C. Mart., was collected in the Municipalities of Serra Branca (7°06'40" S, 36°53'40" W) and the Municipality of São João do Cariri (7°23'27" S, 36°31'58" W), respectively, both located in the state of Paraíba, Brazil. The plants were identified by Professor Dr. José Iranildo de Miranda Melo, and voucher specimens were deposited at the Herbarium Manuel de Arruda Câmara of the Universidade Estadual da Paraíba (accession numbers: HACAM 5316 and HACAM 3243, respectively). Access to the plant material was registered with the Sistema Nacional de Gerenciamento do Patrimônio Genético e do Conhecimento Tradicional Associado (SisGen) under code A18E40E. After identification, the plant material (1.250 kg of E. frankenioides and 1.325 kg of E. glomeratus) was dried, then stabilized in a circulating air oven at 40 °C for 72 h, and then pulverized. The resulting powder was extracted with 96% ethanol for 72 h, and the extractive solution was subsequently dried using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure. Chemicals and reagents The reagents used were 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, gallic acid, ascorbic acid, rosmarinic acid (96% purity), sodium carbonate, aluminum chloride (AlCl3), ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, and ammonium persulfate, all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich® (São Paulo, Brazil). The solvents used were HPLC-grade methanol (Tedia®, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), formic acid (J.T. Baker®, Aparecida de Goiânia, Brazil), acetic acid (J.T. Baker®), phosphoric acid (Proquímios®, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), and ultrapure type I water obtained from a Milli-Q Millipore® purification system. In addition, absolute ethanol P.A. (Neon®, Suzano, Brazil) and Polawax® cream (João Pessoa, Brazil) were used. Quantification of total phenolic content The total phenolic content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. A volume of 0.5 mL of a 10% Folin-Ciocalteu solution was added to 120 μL of the extract (1 mg mL-1). Gallic acid was used as the standard at five different concentrations (25, 50, 75, 100, 150, and 200 μg mL-1). After an 8-min resting period, 400 μL of sodium carbonate (7.5%) was added. The reactions were performed in triplicate and transferred to a 96-well plate. After 120 min, absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a microplate reader spectrophotometer (H1M, BIOTEK®). To calculate the phenolic content, a linear regression equation was derived from the gallic acid calibration curve, and the results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of extract (mg GAE g-1 of sample).14 Quantification of total flavonoid content The flavonoid content was determined using the spectrophotometric method15 employing aluminum chloride (AlCl3). Briefly, 100 μL of a 2.5% AlCl3 solution was added to 100 μL of the extracts (1 mg mL-1) in 96-well plates. After 30 min of incubation in the dark, absorbance was measured at 410 nm using a microplate reader spectrophotometer (H1M, BIOTEK®). The assay was performed in triplicate, and the flavonoid content was calculated using the linear regression equation obtained from the quercetin calibration curve (5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg mL-1). Results were expressed as micrograms of quercetin equivalents per milligram of sample (μg QE mg-1 of sample). DPPH radical scavenging activity The radical scavenging activity of E. frankenioides and E. glomeratus extracts was evaluated using the DPPH method according to Garcez et al.,16 with methanol as the solvent. A volume of 100 µL of a 0.3 mM DPPH solution was added to 100 µL of the extracts at different concentrations (50, 100, 150, 200, 250 µg mL-1), determined by preliminary screening. The same procedure was performed with ascorbic acid as the standard antioxidant. A negative control was performed using 100 µL of DPPH solution and 100 µL of methanol. After 30 min of incubation, the reactions (in triplicate), placed in 96-well plates, were analyzed using a microplate reader (H1M, BIOTEK®) at 518 nm. The results were calculated by determining the percentage of scavenging activity (%SA), according to Equation 1, and extrapolated to the IC50 value, representing the concentration (µg mL-1) of extract required to induce a 50% reduction in DPPH radicals.

ABTS radical scavenging activity The methodology was performed according to Moreira,17 where the ABTS radical was prepared by mixing 7 mM ABTS with 245 mM ammonium persulfate (APS). To confirm the formation of the radical, the reaction mixture was analyzed using a Microplate Reader (H1M, BIOTEK) at 734 nm, showing an absorbance close to 0.700. Then, 10 µL of the samples (at concentrations of 100, 200, 400, 600 and 800 µg mL-1) were added to 190 µL of the ABTS•+ radical solution. Absorbance was measured after 5 min of incubation at room temperature using a spectrophotometer at 734 nm. The same procedure was performed using 2 mM Trolox as the standard. The results were analyzed by calculating the percentage of discoloration of the radical, according to Equation 2. The data were then expressed as the IC50 value, derived from the calibration curves.

In vitro determination of sun protection factor (SPF) SPF was determined in vitro using the method developed by Mansur et al.18 Cream formulations in Polawax® containing 10% of the extracts were prepared in triplicate. These aliquots were diluted in ethanol to obtain a concentration of 0.2 mg mL-1. A scan was performed using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, with absorbance values (ABS) recorded between 290 and 320 nm at 5 nm intervals. SPF was calculated using Equation 3, where the variables EE (erythemal effect spectrum), CF (correction factor), and I (UV radiation intensity) are pre-established in the literature.19 This method quantifies SPF by analyzing the absorbance spectrum of the sunscreen formulation across the specified UV range.

Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) A Shimadzu High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph (HPLC) (Kyoto, Japan) was used, consisting of an LC-20AD solvent pumping unit (flow rate of 0.6 mL min-1), an online degasser DGU-20A5, a system controller CBM-20A, and a diode array detector (DAD) SPD-M20A (190-800 nm). Injections (20 μL) were performed using an SIL-10AF autosampler. Chromatographic separation was conducted on a Kromasil C18 analytical column (5 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 4.6 mm) (Kromasil, Bohus, Sweden). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B). A linear gradient elution (5 to 100% solvent B) was performed over 60 min. The characterization of the compounds was performed using detection with mass spectrometry through an amaZonX ion trap mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. The analysis parameters were as follows: capillary voltage of 4.5 kV, ESI in negative mode, final plate offset of 500 V, nebulizer at 40 psi, drying gas (N2) flow rate of 8 mL min-1, and temperature of 200 °C. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation was performed in the amaZonX system in auto-MS/MS mode, using the enhanced resolution mode. Mass spectra (m/z 50-1000) were recorded every 2 s. Subsequently, the same samples were analyzed in a HPLC system coupled to a micrOTOF II high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometer (HR-ESI-MS) (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA), using the chromatographic conditions as those of the amaZonX system, as previously described.20,21

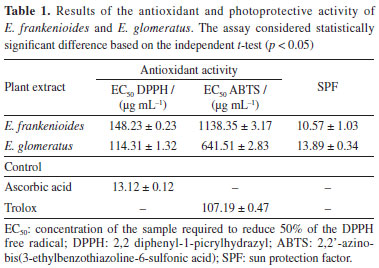

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Total phenolic and flavonoid content of crude ethanolic extract (CEE) of E. frankenioides and E. glomeratus E. glomeratus exhibited a high phenolic content of 172.61 ± 0.87 mg GAE g-1 of extract, whereas E. frankenioides showed 146.74 ± 2.23 mg GAE g-1 of extract. The obtained data were compared with previous studies: Nag and De22 reported a phenolic content of 0.29 mg GAE g-1 of sample for E. nummularius and Padi et al.23 found 17.07 ± 2.28 mg GAE g-1 of sample; both authors using ethanolic extracts. Our findings demonstrate a higher phenolic content for Brazilian species than others belonging to the same genus. Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites with chromophoric groups that are able to absorb ultraviolet radiation. Their electrons can be promoted to higher energy levels upon absorbing quantized energy, resulting in the absorption or dissipation of solar radiation and thus limiting its penetration, a useful feature for the development of sunscreen formulations.24-26 Among the phenolic chemodiversity, flavonoids are some of the most ubiquitous compounds and have previously been reported as main metabolites in Evolvulus species. For this reason, flavonoid content in selected species was assessed: E. frankenioides contained 66.58 ± 0.07 μg QE mg-1, while E. glomeratus presented 55.86 ± 0.28 μg QE mg-1. In comparison, Sundaramoorthy and Packiam27 reported 62.26 ± 0.01 mg QE μg-1 for the methanolic extract of E. alsinoides. Considering these values, E. glomeratus showed higher flavonoid levels than other Evolvulus species, which was confirmed by a statistically significant difference in the independent t-test (p < 0.05). Plants are directly influenced by edaphoclimatic changes. Recent studies28-31 suggest that flavonoids may act in protecting vegetal tissues from UV radiation. The high UV incidence in Brazilian semiarid region might contribute to the remarkable levels of flavonoid content found in E. glomeratus and E. frankenioides. Antioxidant activity of Evulvulus extract and SPF of E. frankenioides and E. glomeratus formulations In order to establish the correlation between the levels of phenolics, antioxidant and photoprotective activities, the extracts were also subjected to DPPH and ABTS assays. In parallel, the determination of SPF in vitro was also carried out, and the results are depicted in Table 1.

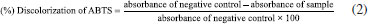

The antioxidant activity of E. glomeratus against the DPPH radical exceeded the results found for E. frankenioides and E. nummularius (EC50 = 350 µg mL-1).32 Previous studies26,33 reported greater activity in DPPH and ABTS for E. alsinoides, exhibiting EC50 of 52.43 and 420 µg mL-1, respectively. Besides, the discrepancy between the results for E. glomeratus and E. frankenioides points out differences in their respective chemical composition. Structure-activity relationship studies of flavonoids, and other phenolic antioxidants, highlight the main features required for activity improvement. Among them, the presence of multiple hydroxyl groups allied to a carbonyl in ring C of the basic nucleus of the flavonoid type flavones and flavonols, conjugated to double bonds in the A and C rings, provides greater stability due to electron delocalization.34-36 The EC50 values of the extracts, though higher than those of the positive controls (ascorbic acid and Trolox), are consistent with expectations, since standards are isolated pure compounds with inherently stronger antioxidant effects. In contrast, plant extracts are complex mixtures of metabolites that may interact with the radicals synergistically or antagonistically, directly affecting the results. Despite the higher EC50 values, the antioxidant performance of the extracts remains relevant in the context of natural product studies. Regarding SPF results, the correlation between the content of phenolic compounds and photoprotective activity is well established in literature for different species applied in the development of sunscreens formulations, such as Mentha × villosa and Passiflora cincinnata.37 Additionally, the presence of compounds bearing catechol moieties, in the extracts, also plays pivotal roles in detection and quantification by classical methods, clearly reflecting on photoprotection.38 Following the evaluation of the extracts alone, they were incorporated into a self-emulsifying base to preliminarily assess their behavior in a pilot formulation and determine whether photoprotection could be enhanced. In this system, both species achieved SPF values superior to 10, a level typically associated with formulations containing synthetic filters. Notably, in this first investigation, conducted with non-specific extraction methods and without enriched fractions, Evolvulus extracts exceeded the minimum requirements established by regulatory agencies, including ANVISA (Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency, Brazil, SPF ≥ 6.0)39 and the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, SPF ≥ 2.0),40 confirming their suitability for natural photoprotective formulations.36,39,40 Chemical characterization of the extract Given the antioxidant and photoprotective activities of the extracts, together with their potential applications, the chemical characterization of Brazilian Evolvulus species becomes essential. The compounds present in the ethanolic extracts of E. glomeratus and E. frankenioides were characterized using HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS and HRMS analysis. The results were compared with published data regarding fragmentation patterns and retention times (Table 2).

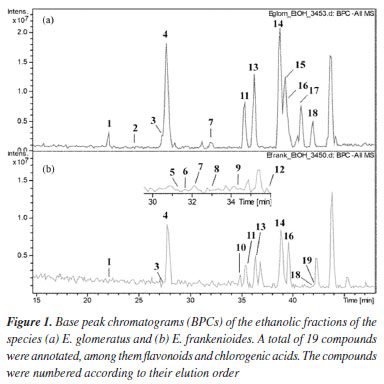

The chromatographic method employed enabled the separation of the main compounds in both samples. The same parameters were used to perform both mass spectrometric experiments, providing information on their respective fragmentation patterns and molecular formulae. A total of 19 phenolic compounds were annotated. The base peak chromatograms (BPC) of both species are shown in Figure 1. Altogether, these results demonstrate the chemical profile of two Evolvulus species, the obtained data were compared with literature reports. The findings are summarized in Table 2.

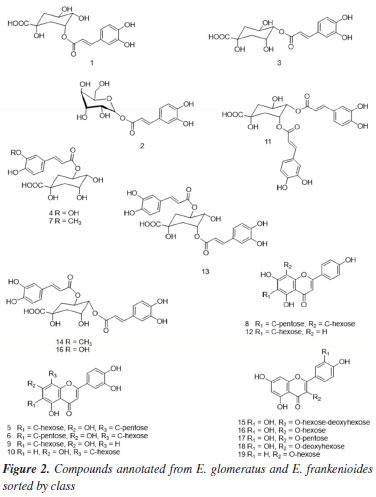

Six caffeoylquinic acid (CQA) derivatives were recognized, including the 3-O-, 4-O-, and 5-O-substituted caffeoyl isomers (compounds 1, 3, and 4, respectively), which were present in both extracts. Compound 1 (tR 22.2 min) presented the [M - H]- ion at m/z 353, accompanied by a base peak in MS2 at m/z 191. The same fragments were also observed for compound 4. The differentiation between these isomers, however, was possible by the presence of the ion at m/z 179, derived from caffeic acid, whose relative intensity was, on average, 47% in compound 1, in contrast to only 5% in compound 4. This pattern is consistent with the assignment of compound 1 to 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid and compound 4 (tR 27.8 min) to 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid, in accordance with the description by Clifford et al.41 Compound 3 was identified as 4-O-caffeoylquinic acid, since 4-O isomers typically exhibit a base peak in MS1 at m/z 173. Compound 2 exhibited the [M - H]- ion at m/z 341, indicating a loss of 162 Da, with the MS2 base peak at m/z 179 and the MS3 base peak at m/z 135, consistent with the presence of a caffeic acid elimination. Based on the fragment ions and retention time, compound 2 was annotated as caffeic acid hexose.42 Compounds 5 and 6, annotated at m/z 579 (tR, 31.5 and 31.9 min), revealed characteristic eliminations of flavonoid-C-glycosides and displayed product ions at m/z 561 ([M - H - 18]-), m/z 489 ([M - H - 90]-), and m/z 459 ([M - H - 120]-), allowing for the assignment of the aglycone portion as luteolin.42 Compound 5 prominently featured the [M - H - 120]-, ion as the main peak compared to [M - H - 90]-, suggesting the presence of a 6-C-hexosyl-8-C-pentosyl substitution. In contrast, for 6, [M - H - 90]- was annotated as the main peak, distinctly characterizing a 6-C-pentosyl-8-C-hexosyl substitution.43 Thus, 5 and 6 were annotated as luteolin-6-C-hexosyl-8-C-pentoside and luteolin-6-C-pentosyl-8-C-hexoside, respectively. Compound 7 exhibited a molecular ion of m/z 367 and was provisionally annotated as 5-O-feruloylquinic acid according to Clifford et al.,41 since the isomers 3-O and 4-O do not produce the m/z 191 fragment ion as the base peak in MS2 spectra. Additionally, the fragment ions in MS3 spectra for the 5-O isomer also support this annotation.44 Compound 8 produced the molecular ion [M - H]- at m/z 563 and fragment ions with m/z 503, 473, and 443, corresponding to mass losses of 60, 90, and 120 Da, which indicated cross-ring cleavages at residues of hexose and pentose. These typical mass losses are indicative of flavonoid C-glycosides, in which the complete aglycone is difficult to cleave from the parent ion, unlike O-glycosides.45 Additionally, the ions m/z 353 and m/z 383 correspond to A + 83 and A + 113, respectively, evidence that the molecular weight of the aglycone is 270. Furthermore, the absence of [M - H- 120]- ions in the MS3 spectra indicated a substituted C-8 hexosyl, as C-8 hexoses fragment preferentially before C-6 pentoses. The ion at m/z 563 was provisionally annotated as apigenin-6-C-pentosyl-8-C-hexoside.46 Compounds 9 and 10, with m/z 447, were detected at 34.2 and 34.9 min, respectively. They exhibited fragmentation characteristics consistent with C-glycosidic flavonoids derived from luteolin. Based on that, 9 and 10 were attributed to isoorientin and orientin, respectively. In addition to the common fragment ions at m/z 357 ([M - H - 90]-) and m/z 327 ([M - H - 120]-), 10 displayed ions at m/z 429 and 411 (low peak intensity), indicative of the successive loss of two water molecules observed in 8-C-glycosides.46 Furthermore, a distinction between 9 and 10 could be proposed, as the [M - H - 120]- ions exhibited higher abundance in 6-C-glycosidic flavonoids compared to the spectra of corresponding 8-C isomers. Compounds 11, 13, and 14 (tR, 35.4; 36.4; and 38.9 min) produced a [M - H]- at m/z 515 and MS2 base peak ions at m/z 353, indicating the loss of the caffeoyl ion, characteristic of dicaffeoylquinic acid isomers. Comparing the fragmentation profile with previously reported data, peak 11 was annotated as 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid. In disubstituted CQA derivatives, the base peak at m/z 173 in MS3 is a typical feature of a caffeoyl moiety substituted at the 4-position. Similarly, the base ion at m/z 173 was also identified in peak 14, which was therefore tentatively assigned as 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid. Besides the retention time, the difference between these two compounds can also be observed through the relative abundance of ions at m/z 179, m/z 191, and m/z 335 (resulting from the dehydration of the m/z 353 ion).43 These findings contrast with the reported data for 3-CQA and 5-CQA derivatives, which are marked by the presence of a base peak at m/z 191, as observed in peak 13. In comparison with literature data, 13 was annotated as 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid. The detection of the ions and fragmentation patterns collectively enables the rapid and reliable annotation of CQA derivatives.44,47 Compound 12 showed an [M - H]- ion at m/z 431. Its MS2 spectrum revealed fragment ions at m/z 341 [M - H - 90]- and a base peak at m/z 311 [M - H - 120]-, suggesting that it is a mono-C-hexose linked to apigenin. The higher abundance of the m/z 341 ion (45%) indicates C-6 glycosylation, as reported in the literature.48 Based on the comparison of fragmentation spectra and previously reported data, peak 12 was assigned as apigenin 6-C-glucoside (isovitexin), since the 8-C-glucoside isomer (vitexin) would present the m/z 341 ion with a very low abundance (around 6%).49 Compound 15, with [M - H]- at m/z 609, was the first quercetin derivative annotated, showing a major fragment at m/z 301, which suggests the presence of two sugar moieties. This ion was attributed to quercetin-O-hexoside-deoxyhexoside (rutin), as reported by Dantas et al.50 Compound 16 was also annotated as a quercetin derivative, with [M - H]- at m/z 463, characterized by a MS2 fragment at m/z 301, attributed to the loss of a hexose unit (162 Da). The aglycone portion of quercetin was confirmed by MS3 fragments at m/z 271 and m/z 255, as well as by product ions resulting from retro Diels-Alder (RDA) cleavage at m/z 179 [M - H - 122]- and m/z 151 [M - H - 150]-, as described by Dantas et al.50 The differential fragmentation observed for 17, with [M - H]- at m/z 433, is consistent with the loss of a pentose moiety ([M - H - 132]-), along with characteristic fragments at m/z 301, 300, 271, and 255, suggesting that this compound corresponds to quercetin-3-O-pentoside.51 For compounds 18 and 19 (tR 42.0 and 42.1 min, respectively), both with [M - H]- at m/z 447, MS2 fragments at m/z 285 and m/z 301 were observed, indicating the loss of an O-glycosidic unit ([M - H - 162]-). Based on comparison with published data, peaks 18 and 19 were provisionally assigned to quercetin-O-deoxyhexoside and kaempferol-O-glycoside, respectively.43 The analysis of fragmentation patterns revealed similar chemical profiles between the ethanolic extracts of E. glomeratus and E. frankenioides. A total of 16 compounds were annotated in E. frankenioides and 12 in E. glomeratus, indicating the metabolite diversity contained in both species. Literature describes Evolvulus as a genus rich in phenolic compounds.52 The extract of E. glomeratus was mainly characterized by the presence of phenolic acids, including mono- and dicaffeoyl isomers. These compounds showed higher relative abundance, suggesting a chemical profile concentrated in a few major metabolites. Additionally, glycosylated flavonoids were detected, although in lower frequency. Literature highlights the antioxidant and photoprotective capacity of mono and diacyl quinic acids derivatives; our results suggest that the presence of this class of compounds may contribute to the superior performance of E. glomeratus.53,54 In contrast, E. frankenioides exhibited a greater diversity of flavonoids, especially C-glycosylated flavones, mainly based on luteolin and apigenin derivatives, although present in lower m/z abundances. The presence of luteolin-6-C-hexoside-8-C-pentoside and luteolin-6-C-pentoside-8-C-hexoside demonstrates the metabolic complexity of this species. The absence of a major compound in this sample is compensated by greater molecular diversity. The chemical structures of annotated compounds are summarized in Figure 2.

These results obtained by chemical profiling directly correlate with the findings for phenolic quantification, antioxidant activity, and SPF determination, since flavonoids and chlorogenic acids, the main classes identified in the samples, inherently display such activities due to their structural features for neutralizing free radicals and mitigating the effects of UV radiation, either directly or indirectly. Furthermore, these compounds may serve as potential chemical markers, which could be valuable for future studies, particularly those aimed at the standardization of extracts for industrial or pharmaceutical applications.

CONCLUSIONS In summary, both species demonstrated diverse chemical composition and exhibited SPF values above 10. Among them, E. glomeratus demonstrated higher phenolic content, stronger in vitro antioxidant capacity, and superior SPF compared to E. frankenioides. Altogether, these findings emphasize the potential of Evolvulus species as valuable natural sources of antioxidant and photoprotective phenolics, with E. glomeratus standing out for its pronounced bioactivity. This work therefore provides important evidence supporting the use of these extracts in the development of safer and more sustainable cosmetic formulations. Finally, the study highlights the ecological and biotechnological value of the Brazilian semi-arid biodiversity and its relevance for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Supplementary material for this work is available at http://quimicanova.sbq.org.br/, as a PDF file, with free access

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT All the necessary data were provided by the authors, they are available in the text and supplementary information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors express their gratitude to the Laboratório Multiusuário de Caracterização e Análise (LMCA), the Laboratório Analítico Multiusuário (LAM), and the Laboratório de Oncofarmacologia (Oncofar) at the Federal University of Paraíba for their valuable support and infrastructure.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS M. B. F. M. N. and T. A. S. were responsible for conceptualization, investigation and writing original draft; J. M. G., C. V. A. S., L. C. O. P. for the methodology and investigation (antioxidant assays and MS data acquisition and curation); J. I. M. M. for the investigation (identification of plant material); H. H. F. K. for the critical reading and editing; M. S. S. for the validation and funding acquisition; J. F. T. for the supervision and project administration.

REFERENCES 1. Kallioğlu, M. A.; Sharma A.; Kallioğlu A.; Kumar S.; Khargotra R.; Singh T.; Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3541. [Crossref] 2. Gromkowska‐Kępka, K. J.; Púscion-Jakubik, A.; Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; Socha, K.; Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2021, 20, 3427. [Crossref] 3. Perez, M.; Abisaad, J. A.; Rojas, K. D.; Marchetti, M. A.; Jaimes, N.; J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 255. [Crossref] 4. Ballestín, S. S.; Bartolomé, M. J. L.; Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 712. [Crossref] 5. Sharma, M.; Sharma, A.; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2023, 1110, 012047. [Crossref] 6. Milutinov, J.; Pavlović, N.; Ćirin, D.; Krstonosić, M. A.; Krstonosić, V.; Molecules 2024, 29, 5409. [Crossref] 7. Ramos, P. S.; Góis, G. V. A.; Cavalcanti, E. B. V. S.; Beltrão, D. M.; Pires, E. A. M.; Reis, M. Y. F. A.; Research, Society and Development 2022, 11, e567111436286. [Crossref] 8. Santos, D.; Buril, M. T.; Rodriguesia 2020, 71, e02432018. [Crossref] 9. Siraj, M. B.; Khan, A. A.; Jahangir, U.; J. Drug Delivery Ther. 2019, 9, 696. [Crossref] 10. Chen, G.-T.; Lu, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, J.-L.; Fan, B.-Y.; Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 823. [Crossref] 11. Pereira, L. C. O.; Abreu, L. S.; e Silva, J. P. R.; Machado, F. S. V. L.; Queiroga, C. S.; do Espírito-Santo, R. F.; de Agnelo-Silva, D. F.; Villarreal, C. F.; Agra, M. F.; Scotti, M. T.; Costa, V. C. O.; Tavares, J. F.; da Silva, M. S.; J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1515. [Crossref] 12. de Oliveira, E. C. P.; Lameira, O. A.; Cordeiro, I. M. C. C.; Ferreira, T. A. A.; Rodrigues, S. M.; Leão, F. M.; dos Santos, J. P.; Neves, R. L. P.; Revista Foco 2023, 16, e991. [Crossref] 13. Soares, L. B.: Potencial Ornamental de Espécies do Estrato Herbáceo-Arbustivo do Cerrado do Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas, MA; Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, Pinheiro, Brasil, 2022. [Link] accessed in October 2025 14. Singleton, V. L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R. M.; Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152. [Crossref] 15. Nicolescu, A.; Bunea, C. I.; Mocan, A.; Anal. Biochem. 2025, 700, 115794. [Crossref] 16. Garcez, F. R.; Garcez, W. S.; Hamerski, L.; Miguita, C. H.; Quim. Nova 2009, 32, 407. [Crossref] 17. Moreira, D. C.; ABTS Decolorization Assay - in vitro Antioxidant Capacity, 2019. [Crossref] 18. Mansur, J. S.; Breder, M. N. R.; Mansur, M. C. d'A.; Azulay, R. D.; An. Bras. Dermatol. 1986, 61, 121. [Link] accessed in October 2025 19. Sayre, R. M.; Agin, P. P.; LeVee, G. J.; Marlowe, E.; Photochem. Photobiol. 1979, 29, 559. [Crossref] 20. de Souza, T. A.; Rodrigues, G. C. S.; de Souza, P. H. N.; Abreu, L. S.; Pereira, L. C. O.; da Silva, M. S.; Tavares, J. F.; Scotti, L.; Scotti, M. T.; Life 2023, 13, 1034. [Crossref] 21. e Silva, J. P. R.; Pereira, L. C. O.; Abreu, L. S.; Lins, F. S. V.; de Souza, T. A.; do Espírito-Santo, R. F.; Barros, R. P. C.; Villarreal, C. F.; de Melo, J. I. M.; Scotti, M. T.; Costa, V. C. O.; Martorano, L. H.; dos Santos Jr., F. M.; Braz Filho, R.; da Silva, M. S.; Tavares, J. F.; J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 2184. [Crossref] 22. Nag, G.; De, B.; J. Complementary Integr. Med. 2008, 5. [Crossref] 23. Padi, P. M.; Adetunji, T. L.; Unuofin, J. O.; Mchunu, C. N.; Ntuli, N. R.; Siebert, F.; S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 149, 170. [Crossref] 24. Vivas, M. G.; Silva, D. L.; De Boni, L.; Bretonniere, Y.; Andraud, C.; Laibe-Darbour, F.; Mulatier, J.-C.; Zaleśny, R.; Bartkowiak, W.; Canuto, S.; Mendonca, C. R.; J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 1753. [Crossref] 25. de Castro, T. N.; Mota, M. D.; Cazedey, E. C. L.; Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quim.-Farm. 2022, 51, 557. [Crossref] 26. Bortoluzzi, A.; Bender, S.; Brazilian Journal of Health Review 2023, 6, 25310. [Crossref] 27. Sundaramoorthy, P. M. K.; Packiam, K. K.; BMC Complementary Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 1. [Crossref] 28. Nenadis, N.; Llorens, L.; Koufogianni, A.; Díaz, L.; Font, J.; Gonzalez, J. A.; Verdaguer, D.; J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2015, 153, 435. [Crossref] 29. Gaiola, L.; Cardoso, C. A. L.; Rev. Fitos 2021, 15, 116. [Crossref] 30. Moreno, A. G.; Woolley, J. M.; Domínguez, E.; de Cózar, A.; Heredia, A.; Stavros, V. G.; Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 12791. [Crossref] 31. Lingwan, M.; Pradhan, A. A.; Kushwaha, A. K.; Dar, M. A.; Bhagavatula, L.; Datta, S.; Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 209, 105300. [Crossref] 32. Pavithra, P. S.; Sreevidya, N.; Verma, R. S.; Indian J. Pharmacol. 2009, 41, 233. [Crossref] 33. Gomathi, D.; Ravikumar, G.; Kalaiselvi, M.; Vidya, B.; Uma, C.; Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 21, 453. [Crossref] 34. Mechqoq, H.; Hourfane, S.; El Yaagoubi, M.; El Hamdaoui, A.; Msanda, F.; Almeida, J. R. G. S.; Rocha, J. M.; El Aouad, N.; Cosmetics 2022, 9, 94. [Crossref] 35. El-fayoumy, E. A.; Shanab, S. M. M.; Gaballa, H. S.; Tantawy, M. A.; Shalaby, E. A.; BMC Complementary Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 51. [Crossref] 36. Moazzen, A.; Öztinen, N.; Ak-Sakalli, E.; Koşar, M.; Heliyon 2022, 8, e10467. [Crossref] 37. de Oliveira Júnior, R. G.; Reis, S. A. G. B.; de Oliveira, A. P.; Ferraz, C. A. A.; Rolim, L. A.; Lopes, N. P.; Rocha, J. M.; El Aouad N.; Kritsanida, M.; Almeida, J. R. G. S.; Chem. Biodiversity 2024, 21, e202401271. [Crossref] 38. Gomes, J. M.; Terto, M. V. C.; do Santos, S. G.; da Silva, M. S.; Tavares, J. F.; Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 110. [Crossref] 39. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA); Manual de Regularização de Protetores Solares, 2024. [Link] accessed in October 2025 40. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); FDA Proposes Sunscreen Regulation Changes, 2019. [Link] accessed in October 2025 41. Clifford, M. N.; Johnston, K. L.; Knight, S.; Kuhnert, N.; J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2900. [Crossref] 42. Kang, J.; Price, W. E.; Ashton, J.; Tapsell, L. C.; Johnson, S.; Food Chem. 2016, 211, 215. [Crossref] 43. AlGamdi, N.; Mullen, W.; Crozier, A.; Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 248. [Crossref] 44. Narváez-Cuenca, C.-E.; Vincken, J.-P.; Gruppen, H.; Food Chem. 2012, 130, 730. [Crossref] 45. Waridel, P.; Wolfender, J.-L.; Ndjoko, K.; Hobby, K. R.; Major, H. J.; Hostettmann, K.; J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 926, 29. [Crossref] 46. Cao, J.; Yin, C.; Qin, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, D.; J. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 49, 1010. [Crossref] 47. Jaiswal, R.; Sovdat, T.; Vivan, F.; Kuhnert, N.; J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5471. [Crossref] 48. Ferreres, F.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Andrade, P. B.; Valentão, P.; Tomás-Barberán, F. A.; J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1161, 214. [Crossref] 49. Beszterda, M.; Frański, R.; Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 26, 369. [Crossref] 50. Dantas, C. A. G.; Abreu, L. S.; da Cunha, H. N.; Veloso, C. A. G.; Souto, A. L.; Agra, M. F.; Costa, V. C. O.; da Silva, M. S.; Tavares, J. F.; Phytochem. Anal. 2021, 32, 1011. [Crossref] 51. Fraige, K.; Dametto, A. C.; Zeraik, M. L.; de Freitas, L.; Saraiva, A. C.; Medeiros, A. I.; Castro-Gamboa, I.; Cavalheiro, A. J.; Silva, D. H. S.; Lopes, N. P.; Bolzani, V. S.; Phytochem. Anal. 2018, 29, 196. [Crossref] 52. Gupta, P.; Sharma, U.; Gupta, P.; Siripurapu, K. B.; Maurya, R.; Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1116. [Crossref] 53. Oh, J. H.; Karadeniz, F.; Lee, J. I.; Seo, Y.; Kong, C.-S.; Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 763. [Crossref] 54. Kim, K. J.; Kim, D.-O.; Food Chem.: X 2025, 28, 102506. [Crossref] |

On-line version ISSN 1678-7064 Printed version ISSN 0100-4042

Qu�mica Nova

Publica��es da Sociedade Brasileira de Qu�mica

Caixa Postal: 26037

05513-970 S�o Paulo - SP

Tel/Fax: +55.11.3032.2299/+55.11.3814.3602

Free access