Artigo

| Investigating cholagogue and choleretic activity of Peumus boldus |

|

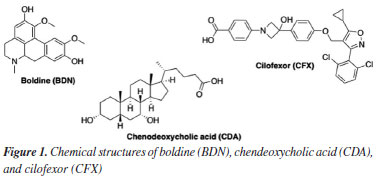

Raphael S. F. SilvaI,* I. Colégio Militar do Rio de Janeiro, 20550-010 Rio de Janeiro - RJ, Brasil Received: 08/30/2024 *e-mail: silvaferreirasallesraphael@gmail.com; tanosfranca@gmail.com This study aimed to utilize molecular modeling and theoretical chemistry methods to contribute to the elucidation of the mechanism of action of boldine, an alkaloid present in the Peumus boldo plant. Boldo holds a special place in traditional medicinal practices throughout Brazil and has been officially recognized as medicinal plant. It is traditionally indicated for choleretic and cholagogue effects, among other digestive disorders. Literature has provided experimental evidence demonstrating that boldine can bind to the farnesoid X receptor, a key player in the production and excretion of bile. Our in silico study revealed that boldine exhibits stable non-bonded interactions like those calculated for the endogenous ligand chenodeoxycholic acid and the synthetic agonist colifexor, supporting what has been experimentally observed in the literature. The packages MOPAC, AutoDock, GROMACS and g_mmpbsa were employed for structural optimization, molecular docking, molecular dynamics and bond energy calculations respectively. This study demonstrates the application of theoretical chemistry and molecular modeling methods, including molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA), in identifying molecular targets and providing insights into the bioactivities of natural products. INTRODUCTION Boldo (Peumus boldo Mol.) is a medicinal plant with widespread and established usage throughout South America. This plant originated from Chile and became known in Western cultures through interactions between Spanish colonizers and the native Mapuche people. While the etymology remains controversial, the term "boldo" itself finds its roots in the Mapuche language. The properties of the plant were systematically described by the Jesuit priest Juan Ignacio Molina in the 18th century.1 In Brazil, boldo is referred to as "boldo do Chile" (Chilean boldo), as it is frequently mistaken for the species Coleus barbatus, commonly known as "boldo da terra" or false boldo. Boldo holds a place in traditional medicinal practices throughout Brazil and has been officially documented in the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia since its inaugural edition. Popularly used in Brazil as a choleretic and cholagogue, boldo is employed to address various digestive disorders.2-6 Medicines containing boldo extract as an active ingredient are incorporated into the herbal medicine formulary of Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA).7 Consequently, these medications are officially recognized as herbal medicines and are manufactured by several pharmaceutical industries in the country. They are available in various forms such as tablets, oral solutions, and effervescent tablets.7,8 The main secondary metabolite of boldo is the alkaloid boldine (BDN) (Figure 1), which exhibits various biological activities such as antioxidant properties,9 hypoglycemic effects,10 osteogenetic potential,11 and cosmetic applications.12 Recently, BDN has shown promise as a molecule for the treatment of neurological disorders such as epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease.13,14

Several studies15-17 have gathered experimental evidence to demonstrate that boldo, and consequently BDN, present choleretic and cholagogue effects. However, there are also studies18 that have concluded exactly the opposite, suggesting that boldo or even BDN lack any choleretic or cholagogue activity. More robust evidence regarding the effects of BDN on bile production was published by Cermanova et al.19 Their experimental findings demonstrated that BDN enhances bile production, and this effect may be associated with the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a bile acid receptor whose one of the endogenous agonists is the chenodeoxycholic acid (CDA) (Figure 1). Besides, an FXR agonist named cilofexor (CFX) (Figure 1) has recently garnered attention as a potential therapeutic target for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).20-24 Considering the aforementioned points, as boldo is a plant traditionally used in Brazil, alongside the still controversial mechanism of action of BDN at the molecular level and the therapeutic potential of FXR agonists for treating PSC and NASH, this study aimed to investigate the interactions and free energy of binding between BDN and FXR using molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) calculations. The results obtained were compared to the endogenous CDA and the experimental FXR agonist CFX (Figure 1).

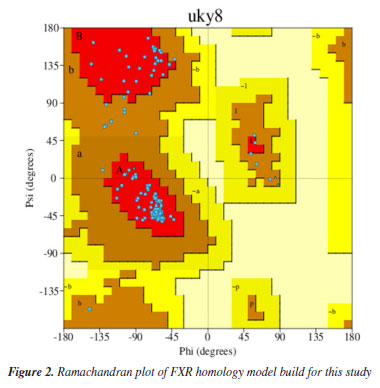

EXPERIMENTAL Homology modeling The crystallographic structure of the Homo sapiens sapiens farnesoid X receptor (HssFXR) co-crystallized with CDA was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) server under the code 6HL1.25 Since the protein structure was incomplete, it was necessary to construct a homology model through the structural alignment between the corresponding FASTA sequence (downloaded from the PDB server)25 to its incomplete crystallographic structure, using the Swiss-PDB viewer program,26 followed by submission to the optimize mode of the Swiss-Model server.27 The further model validation was performed using the PROCHECK software28 hosted in the PDBsum server. The Ramachandran plot obtained for the validated model is shown in Figure 2.

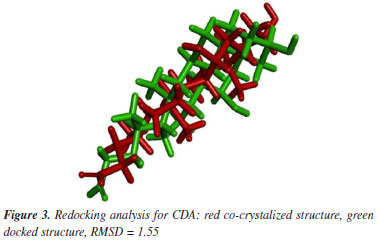

Molecular docking calculations The 2D chemical structures of BDN, CDA, and CFX were drawn and submitted to calculation of their protonation states and partition coefficient octanol/water (LogP) under physiologic pH (7.4) using the Chemicalize server.29 The dominant species at pH 7.4 for CDA and CFX were the ones with the carboxyl groups ionized, and net charge = −1, while for BDN the dominant species was the one with the nitrogen atom protonated and net charge = +1. The 3D chemical structures of the dominant ligand species at pH 7.4 were built using the ChemSketch version 2022.1.2 (ACD/Labs 2022),30 and submitted to the geometry optimization and partial atomic charges calculations through the PM7 (Parametric Method 7) semi-empirical method performed with the MOPAC2016 program.31,32 After partial atomic charges calculations, molecular docking was performed employing the AutoDock suite:33 AutoDockTools (ADT) for files preparation and AutoDock 4.2 to run the docking calculations. Redocking of the CDA co-crystallized on HssFXR afforded a root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of 1.55 Å (Figure 3) which is ≤ 2.0 Å and, therefore, considered enough to validate the docking protocol used according to the literature.34

For all dockings performed in this study, the binding site was restricted into a cubic grid box with an edge = 30 Å centered in the co-crystalized ligand which the coordinates were x = -1.3579, y = 1.0506 and z = 7.6842. All the residues within this grid box were considered flexible. The parameters used for AutoDock 4.233 docking calculations were as follows: Lamarckian genetic algorithm was used for the conformation search; the number of evaluations was set at 25 and the other parameters were set to default; all docking parameters were saved as the .DPF file; the best-predicted conformation (lowest estimated docking energy) for each ligand and each receptor was selected and used for molecular docking visualization. The receptor-ligand complexes were generated in ADT 4.2,33 saved as a .PDBQT file and after converted in a .PDB file and visualized using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE)® software.35 The best protein-ligand complexes (most negative docking energies) were selected for the further rounds of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Molecular dynamics simulations The MD simulations were performed applying the bonded and non-bonded parameters for the all-atom force field OPLS-AA (optimized potentials for liquid simulations all atoms) inside the GROMACS 5.1.4 software.36 The three-dimensional coordinates and topologies of the protein were generated by the pdb2gmx software, which is part of the GROMACS 5.1.4 package.37,38 Since the OPLS-AA force field has no parameters for the ligands studied, the programs ACPYPE39 and MKTOP40 were used to generate topology and coordinates files for these ligands. The restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) method parameterized to reproduce the Hartree-Fock (HF) method and basis set 6-31G*41-43 was applied to calculate the atomic charges. The complexes protein/ligand were confined inside dodecahedron boxes under periodic boundary conditions (PBC) where the effect of the solvent was reproduced by the water model TIP4P.44-46 The box volume of each system was 3,432 nm3, the average number of TIP4P water molecules was around 101,000, and the electrostatic neutralization was achieved through addition of Na+ atoms. All systems were submitted to two minimization steps, the first with position restrained (PR) and the second without PR, using the steepest descent algorithm with the convergence criterion of 100.00 kJ mol-1 nm-1. The equilibration of pressure and temperature was achieved through 100 ps of simulation using the canonical ensemble (NVT), keeping the number of particles, volume, and temperature constant, followed by more 100 ps with an isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT), keeping the number of particles, pressure, and temperature constant.47 After the equilibration steps, all systems were submitted to production steps of 200 ns performed at 310 K and 1 bar, using 2 fs of integration time with the lists of pairs being updated at every 5 steps. The cut-off for Lennard Jones and Coulomb interactions were between 0.0 and 1.2 nm. The leap-frog algorithm was used in the production step with the Nose-Hoover thermostat48 (τ = 0.5 ps) at 310 K and the Parrinello Rahman barostat49 (τ = 2.0 ps) at 1 bar. All Arg and Lys residues were assigned with positive charges and all Glu and Asp residues were assigned with negative charges. The GraphPad Prism® software50 was used to generate the plots of energy, root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and H-bonds, while the Visual Molecular Dynamics software50 was used to visualize the simulation trajectories. Binding energies Binding energies involved in the stabilization of the protein/ligand complexes were calculated by the MM-PBSA method employing the g_mmpbsa software integrated with GROMACS 5.1.4.51-54 Dielectric constants of 8, 80, and 1 were considered for solute (complex protein/ligand), solvent (water), and vacuum, respectively. Free energy (ΔG) nonpolar includes repulsive and attractive forces between the solute (generated by cavity formation) and solvent (generated by van der Waals (VDW) interactions). The solvent accessible surface area (SASA) was the only model used for ΔGnonpolar calculation, with surface tension simulated at 2.26778 kJ mol-1 nm2 and probe radius = 0.14 nm. The number of grid points per area unit was set to 10 for ΔGpolar and 20 for ΔGnonpolar.39,55,56

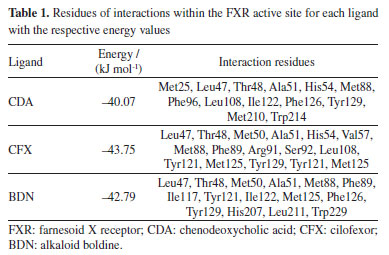

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Docking studies The docking results reported in Table 1 show that the best pose of BDN ranked better (more negative) than CDA and close the experimental HssFXR inhibitor CFX. Besides, all residues observed in interactions with BDN were also observed in interactions with CDA and CFX. This suggests that BDN might qualify as a potential HssFXR inhibitor.

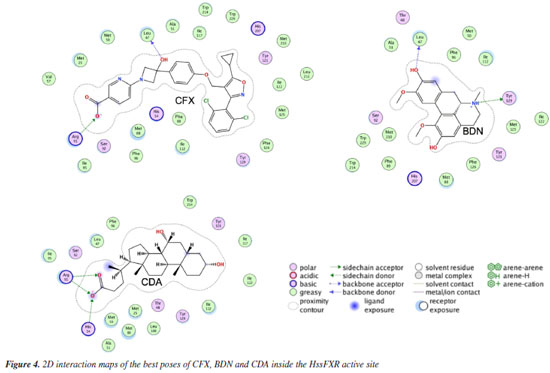

The 2D interaction maps (Figure 4) show that the main interactions observed for the best pose of CDA primarily comprised H-bonds of the carboxyl moiety with His54 and Arg91, and polar interactions with Thr48, Ser92 and Tyr129. For CFX, the main interactions included the H-bonds between Leu47 and the OH of the azacyclobutane ring, and between Arg91 and the carboxyl group followed by polar interactions with His54, Ser92, Tyr121 and His207. The best pose of BDN on this turn H-bonded to Leu47 (with one of the aromatic OH) and Try129 (to the tertiary amine) and polar interactions with Thr48, Ser92 and Tyr121.

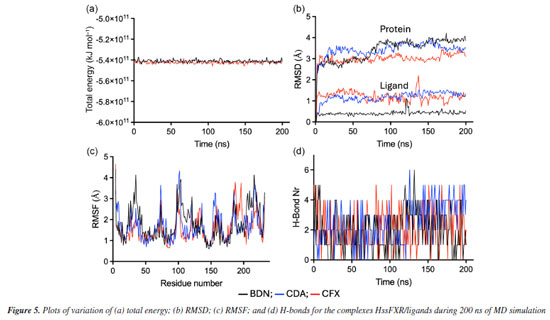

MD simulations The total energy graphs obtained for the three complexes protein-ligand during the MD simulations consistently exhibited negative values, Figure 5a, indicating that internal interactions within the systems prevailed over tensions and repulsions, and pointing to stabilization of the MD simulations. The temporal RMSD plotted in Figure 5b show that the maximal fluctuations never passed 4.5 and 2.2 Å for protein and ligand, respectively, while the local fluctuations were always below 1.0 Å in both cases. Besides, the RMSF plotted in Figure 5c, shows no amino acid fluctuation above 4.5 Å. These results suggest that the three ligands stabilized inside the inside HssFXR active site during the MD simulations, corroborating with the docking studies.

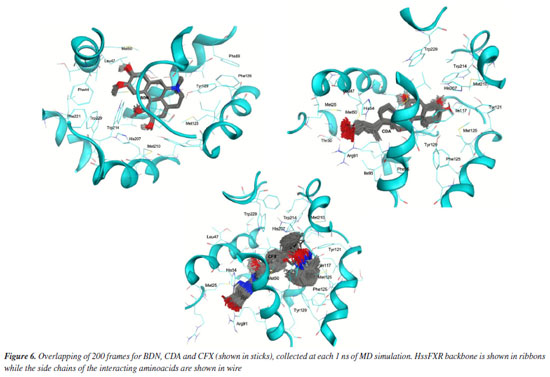

Comparing the dynamical behavior of the ligands it is noticeable the remarkable stability of BDN compared to the other ligands, see Figure 5b. This ligand showed local fluctuation mostly around 0.25 Å and total fluctuations mostly below 0.5 Å, while CDA and CFX fluctuated locally around 0.5 Å and showed maximal fluctuations of up to 2.0 Å. This trend can be clearly visualized in the overlapping of frames from the MD simulations in Figure 6 and might be correlated with the number of rotatable bonds present in each ligand (which certainly increase flexibility), with CFX possessing twelve, CDA containing ten, and BDN featuring only five.

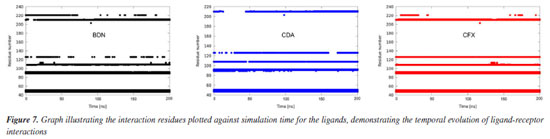

The plots of number of H-bonds formed during the MD simulations, Figure 5d, show similar profiles with average numbers around 2 in all cases. BDN and CDA formed up to 6 H-bonds while CFX achieved 5. This result corroborates the affinities of the ligands towards HssFXR observed in the docking and RMSD and RMSF results and suggest that the three compounds can stablish strong interactions in the active site. A more insightful approach to assess whether a given ligand can maintain stable interactions with active site residues throughout the simulation time is to plot a time versus residue number graph. These graphs for the three ligands are presented in Figure 7, where it is evident that all three ligands remain within the active site, interacting with aminoacids at the same five distinct regions simultaneously during the whole MD simulation.

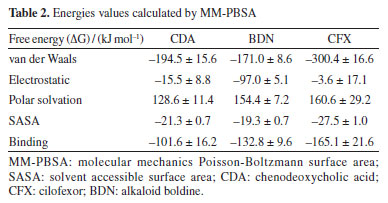

Binding energy The results obtained from the MD simulations suggest that BDN binds to the active site in a stable manner and exhibits similar behavior to the endogenous agonist CDA and the synthetic agonist CFX. However, it is important to note that the GROMACS package is unable to directly calculate the binding free energy (ΔGbond) between a ligand-receptor complex. For this the method employing MM-PBSA calculations is usually employed to provide a better (and more accurate) estimate of the bond strength between ligand and receptor. According to our MM-PBSA results (Table 2) BDN has showed a total ΔGbond value of -132.8 ± 9.6 kJ mol-1, better (more negative) than CDA (-101.6 ± 16.2 kJ mol-1) and worse than CFX (-165.1 ± 21.6 kJ mol-1). The van der Waals contributions were the most important for the three compounds but for BDN the electrostatic ranked second while to the others it ranked third. These results align with the docking and MD simulations and confirm BDN as potential binder to HssFXR, despite showing some differences in binding mode, and support the experimental results reported by Cermanova et al.19

CONCLUSIONS Our calculations demonstrated that BDN can bind to the HssFXR receptor similarly to the endogenous ligand CDA, thereby supporting experimental findings reported in the literature. Furthermore, the results revealed a behavior of BDN akin to CFX, suggesting the potential utility of BDN in the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. This article illustrates the utilization of theoretical computational chemistry methods to elucidate the molecular target underlying the choleretic and cholagogue activity associated with BDN, the primary alkaloid of Peumus boldo. By demonstrating the application of molecular modeling in pharmacognosy and ethnobotany studies, this research highlights the potential of computational approaches to provide insights into natural product pharmacology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS T. C. C. F. thanks the support from Brazilian agency Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grant No. 305432/2022-2). This work was also supported by the Excellence project PrF̌UHK 2216/2023-2024

REFERENCES 1. Speisky, H.; Cassels, B. K.; Pharmacol. Res. 1994, 29, 1. [Crossref] 2. Barbosa, M. C. S.; Belletti, K. S.; Corrêa, T. F.; Santos, C. M.; Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2001, 11, 1. [Crossref] 3. Ruiz, A. L. T.; Taffarello, D.; Souza, V. H.; Carvalho, J. E.; Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2008, 18, 295. [Crossref] 4. Lazarotto, M. S.; Pagno, A. R.; Schneider, T. M.; Copetti, T. S.; Revista Interdisciplinar em Ciências da Saúde e Biológicas 2021, 5, 35. [Crossref] 5. do Amaral, J. F.; Pafo, F.; da Silva, A. P.; da Silva, F. M.; Bandeira, N. C. R.; Oliveira, L. C.; de Oliveira, E. G.; Cavalcante Neto, L. C.; da Silva, F. D. F. C.; dos Santos, A. J. M.; Pinto, O. R. O.; International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science 2023, 10, 4. [Crossref] 6. Medeiros, T. K. C.; de Castro, P. F. R.; Vieira, A. C. M.; Research, Society and Development 2022, 11, e211111637856. [Crossref] 7. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA); Formulário de Fitoterápicos da Farmacopeia Brasileira, 2ª ed.; ANVISA: Brasília, 2021. [Link] accessed in December 2024 8. Cesar, A. M. N.; PI 0402929-1 A, 2004. 9. Abouelela, M. B.; Naimy, R. A.; Elshafey, O. A.; Mahmoud, M. M.; Elgez, M. M.; Ahmed, M. M.; Abdallah, N. M.; Boshra, Y. A.; Mohamed, A. S.; Saad, E. E.; Abdelhay, M. I.; Ali, A. M.; El Sayed, E.; Mohamed, O. E.; Mohamed, S. E.; Mohamed, A.; ElGindi, O.; ERU Research Journal 2023, 2, 308. [Crossref] 10. Silva, L. C. L.; de Souza, G. H.; Pateis, V. O.; Ames-Sibin, A. P.; Silva, B. P.; Bracht, L.; Comar, J. F.; Peralta, R. M.; Bracht, A.; Sá-Nakanishi, A. B.; Int. J. Hepatol. 2023, 2023, 1283716. [Crossref] 11. Ellies, D.; Kimball, F. R.; US pat. 20140023653, 2014. 12. Lintner, K.; WO 02066000, 2002. 13. Akotkar, L.; Aswar, U.; Ganeshpurkar, A.; Raj, R.; Pawar, A.; Neurochem. Res. 2023, 48, 3283. [Crossref] 14. Cardoso, C.; Toro-Chacon, C.; WO 2021159011, 2021. 15. Delso-Jimeno, J. L.; An. Inst. Farmacol. España 1956, 5, 395. [Link] accessed in December 2024 16. Levy-Appert-Collin, M. C.; Levy, J.; J. Pharm. Belg. 1977, 32, 13. [Link] accessed in December 2024 17. Pirtkien, R.; Surke, E. G. S.; Die Medizinische Welt 1960, 33, 1417. [Link] accessed in December 2024 18. Lanhers, M. C.; Joyeux, M.; Soulimani, R.; Fleurentin, J.; Sayag, M.; Mortier, F.; Younos, C.; Pelt, J. M.; Planta Med. 1991, 57, 110. [Crossref] 19. Cermanova, J.; Kadova, Z.; Zagorova, M.; Hroch, M.; Tomsik, P.; Nachtigal, P.; Kudlackova, Z.; Pavek, P.; Dubecka, M.; Ceckova, M.; Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015, 285, 12. [Crossref] 20. Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Wei, H.; Dai, S.; Qu, L.; Chen, X.; Guo, M.; Chen, Y.; Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 595, 1. [Crossref] 21. Trauner, M.; Gulamhusein, A.; Hameed, B.; Caldwell, S.; Shiffman, M. L.; Landis, C.; Eksteen, B.; Agarwal, K.; Muir, A.; Rushbrook, S.; Lu, X.; Xu, J.; Chuang, J.; Billin, A. N.; Li, G.; Chung, C.; Subramanian, G. M.; Myers, R. P.; Bowlus, C. L.; Kowdley, K. V.; Hepatology 2019, 70, 788. [Crossref] 22. Loomba, R.; Noureddin, M.; Kowdley, K. V.; Kohli, A.; Sheikh, A.; Neff, G.; Bhandari, B. R.; Gunn, N.; Caldwell, S. H.; Goodman, Z.; Wapinski, I.; Resnick, M.; Beck, A. H.; Ding, D.; Jia, C.; Chuang, J.; Huss, R. S.; Chung, C.; Subramanian, G. M.; Myers, R. P.; Patel, K.; Borg, B. B.; Ghalib, R.; Kabler, H.; Poulos, J.; Younes, Z.; Elkhashab, M.; Hassanein, T.; Iyer, R.; Ruane, P.; Shiffman, M. L.; Strasser, S.; Wong, V. W.; Alkhouri, N.; Hepatology 2021, 73, 625. [Crossref] 23. Patel, K.; Harrison, S. A.; Elkhashab, M.; Trotter, J. F.; Herring, R.; Rojter, S. E.; Kayali, Z.; Wong, V. W. - S.; Greenbloom, S.; Jayakumar, S.; Shiffman, M. L.; Freilich, B.; Lawitz, E. J.; Gane, E. J.; Harting, E.; Xu, J.; Billin, A. N.; Chung, C.; Djedjos, C. S.; Subramanian, G. M.; Myers, R. P.; Middleton, M. S.; Rinella, M.; Noureddin, M.; Hepatology 2020, 72, 58. [Crossref] 24. Polyzos, S. A.; Xanthopoulos, K.; Kountouras, J.; Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 20, 111. [Crossref] 25. Merk, D.; Sreeramulu, S.; Kudlinzki, D.; Saxena, K.; Linhard, V.; Gande, S. L.; Hiller, F.; Lamers, C.; Nilsson, E.; Aagaard, A.; Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2915. [Crossref] 26. Guex, N.; Peitsch, M. C.; Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714. [Crossref] 27. Schwede, T.; Kopp, J.; Guex, N.; Peitsch, M. C.; Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3381. [Crossref] 28. Laskowski, R. A.; Jabłońska, J.; Pravda, L.; Vařeková, R. S.; Thornton, J. M.; Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 129. [Crossref] 29. Chemicalize; ChemAxon Ltd., Budapest, 2018. [Link] accessed in December 2024 30. ChemSketch, version 2022.1.2; Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., Toronto, Canada, 2022. 31. Stewart, J. J. P.; MOPAC2016; Stewart Computational Chem, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2016. [Link] accessed in December 2024 32. Stewart, J. J. P.; J. Mol. Model. 2013, 19, 1. [Crossref] 33. Morris, G. M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M. F.; Belew, R. K.; Goodsell, D. S.; Olson, A. J.; J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785. [Crossref] 34. Dias, R.; de Azevedo Junior, W.; Curr. Drug Targets 2008, 9, 1040. [Crossref] 35. Labute, P.; Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), version 6; Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada, 2024. [Link] accessed in December 2024 36. Berendsen, H. J.; van der Spoel, D.; van Drunen, R.; Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 91, 43. [Crossref] 37. Hess, B.; Kutzner, C.; van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 435. [Crossref] 38. van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A. E.; Berendsen, H. J. C.; J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701. [Crossref] 39. da Silva, J. A. V.; Nepovimova, E.; Ramalho, T. C.; Kuca, K.; França, T. C. C.; J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 1018. [Crossref] 40. Ribeiro, A. A.; Horta, B. A.; de Alencastro, R. B.; J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2008, 19, 1433. [Crossref] 41. Bayly, C. I.; Cieplak, P.; Cornell, W.; Kollman, P. A.; J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 10269. [Crossref] 42. Cornell, W. D.; Cieplak, P.; Bayly, C. I.; Kollman, P. A.; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 9620. [Crossref] 43. Wang, J.; Cieplak, P.; Kollman, P. A.; J. Comput. Chem. 2000, 21, 1049. [Crossref] 44. Martínez, L.; Borin, I. A.; Skaf, M. S. In Métodos de Química Teórica e Modelagem Molecular; Morgon, N. H.; Coutinho, K., eds.; Livraria da Física: São Paulo, 2007, ch. 12. 45. Harrach, M. F.; Drossel, B.; J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 174501. [Crossref] 46. Jorgensen, W. L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J. D.; Impey, R. W.; Klein, M. L.; J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926. [Crossref] 47. Bosko, J. T.; Todd, B. D.; Sadus, R. J.; J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 34905. [Crossref] 48. Evans, D. J.; Holian, B. L.; J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 4069. [Crossref] 49. Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A.; J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182. [Crossref] 50. GraphPad Prism, version 10; GraphPad Software, Boston, USA, 2021; Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K.; J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33. [Crossref] 51. Kaminski, G. A.; Friesner, R. A.; Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W. L.; J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 6474. [Crossref] 52. Hansen, N.; van Gunsteren, W. F.; J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 2632. [Crossref] 53. Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Mol. Inf. 2012, 31, 114. [Crossref] 54. Kumari, R.; Kumar, R.; J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1951. [Crossref] 55. Cuya, T.; Baptista, L.; França, T. C. C.; J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 36, 3843. [Crossref] 56. de Almeida, J. S.; Dolezal, R.; Krejcar, O.; Kuca, K.; Musilek, K.; Jun, D.; França, T. C. C.; Toxins 2018, 10, 389. [Crossref]

Editor handled this article: Nelson H. Morgon |

On-line version ISSN 1678-7064 Printed version ISSN 0100-4042

Qu�mica Nova

Publica��es da Sociedade Brasileira de Qu�mica

Caixa Postal: 26037

05513-970 S�o Paulo - SP

Tel/Fax: +55.11.3032.2299/+55.11.3814.3602

Free access