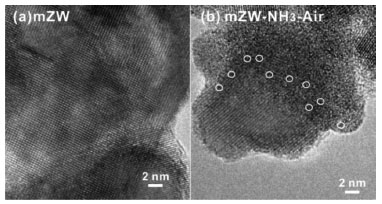

Artigo

| Improved acidity of mesoporous ZrO2-WO3 through NH3-AIR subsection-calcination treatment |

|

Chengwei Jin; Bonan Xu; Biao Xu; Jianzhong Guo; Sha Li* Department of Chemistry, College of Chemistry and Materials Engineering, Zhejiang A & F University, 311300 Hangzhou, China Received: 03/31/2023 *e-mail: shali@zafu.edu.cn ZrO2-WO3 mixed metal oxides are important solid acid catalysts, and typically, ammonia gas calcination reduces their acidity. However, in this study, we introduce an updated NH3 calcination technique that can increase the acidity of mesoporous ZrO2-WO3 solid acids. Their structures and acid properties were thoroughly characterized through X-ray diffraction (XRD), N2 adsorption measurement, pyridine-adsorbed infrared spectroscopy (Py-IR), temperature-programmed desorption of ammonia (NH3-TPD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-Vis-DRS) analysis. The resulting materials exhibit remarkable activity in the Friedel-Crafts (F-C) reaction of anisole and benzyl alcohol. Our investigations showed that the subnanometer WOx clusters act as the most active sites for the F-C reaction, and NH3-air calcination is essential for the formation of WOx clusters. This treatment not only enhances acidity but also provides a novel method of obtaining acidic ZrO2-WO3 mixed metal oxides. Most importantly, it presents a fresh approach for regulating the formation of WO3 clusters and catalytic activity. INTRODUCTION Since the discovery by Hino and Arata1,2 that tungstated zirconia exhibits strong acidic properties, it has gained considerable attention as a solid acid catalyst.3 WO3-ZrO2 is a compelling option for various applications in the petrochemical industry, due to the strong acidity and high thermal stability.4 The acidity of WO3-ZrO2 can be adjusted through various means, such as modifying the phase of ZrO2,5 varying the amount of tungsten loading,6 regulating calcination temperature,7 adding some metal promoters (e.g., Fe and Al),8,9 as well as treating with H2SO4 and H3PO4,10 and controlling the preparation conditions. There are several methods for synthesizing tungstated zirconia, including impregnation, coprecipitation, hydrothermal synthesis and sol-gel techniques. It has been deduced that the subnanometre (0.8-1.0 nm) Zr-WOx clusters are responsible for the strong acidity and high activity of WO3-ZrO2 solid acid catalysts.11 It is well-known that calcination atmosphere can have a significant impact on the structure and acidity of oxides. For instance, H2 or N2 calcination can induce a high amount of Zr3+ in ZrO2 which can facilitate the formation of high acidic tungsten species that enhance the catalytic activity of WO3-ZrO2 catalyst in transesterification.12 The amount of W atoms that migrate to the surface and the interaction degree between WOx species and ZrO2 surface can be controlled by modulating the calcination temperature and atmosphere.3 Typically, a reducing atmosphere allows for the quantitative reduction of tungsten atoms to W5+, resulting in the formation of Zr-WOx clusters that act as active sites. Thermal treatment of oxide under a flow of ammonia, also known as nitridation, is an effective way to modify the acid-base properties of catalysts. Li and co-authors13 proposed that Brønsted acidity could be effectively adjusted by nitridation and found that nitrided catalyst possessed lower Brønsted acidity. Xia and Mokaya14 demonstrated that introduction of NHx species into MCM-48 generated basic sites and the amount of acid and basic sites could be adjusted by tuning the nitridation conditions. Wiame et al.15 deduced that nitridation of aluminovanadate would produce basic surface sites detected by IR spectroscopy. Wang and Liu16 showed the intensity of basicity increased with prolonged nitridation times under ammonia and was consistent with the nitrogen content. Ernst and co-authors17 indicated that basic sites in the nitrided zeolite beta were Si-NH2 and the basicity depended on the ammonia treatment temperature. Zhang and co-authors18 showed that nitrogen-incorporated titanium silicalite-1 could decrease surface acidic sites. Generally, ammonia gas calcination reduces acidity. To the best of our knowledge, no previous reports have explored the production of additional Brønsted acid sites in WO3-ZrO2 calcined in air following NH3 calcination. In this study, we present a NH3-air subsection-calcined treatment for the preparation of homogeneous, mesoporous ZrO2-WO3 solid acid. NH3-Air subsection-calcined ZrO2-WO3 demonstrates increased Brønsted acidic sites and significantly improved catalytic performance in Friedel-Crafts (F-C) reaction of anisole and benzyl alcohol which proceeds on strong or moderate strong Brønsted acid sites.19 NH3-Air subsection treatment can induce the generation of WOx clusters active sites. Moreover, both NH3 and air are indispensable for the improved acidity.

EXPERIMENTAL Catalysis preparation Mesoporous ZrO2-WO3 materials with a W/Zr molar ratio of 1:9 (denoted as mZW) were prepared by sol-gel method with Zr(BuO)4 (TBOZ) and WCl6 as precursors.20,21 Mesoporous ZrO2-WO3 materials with different surfactant (denoted as mZW-S) were synthesized by the similar method, except for the adding of pluronic (F127) or polyoxyl lauryl ether (brij 30) as structure directing agents. NH3-Air calcined ZrO2-WO3 (mZW-NH3-air) was prepared by calcining mZW in ammonia gas and subsequently in air. Specifically, 1.0 g mZW powder was thermally treated in a quartz tube with a stream of pure ammonia (40 mL min-1) going through the tube at 600 ºC (a ramp rate of 1 ºC min-1) for 24 h. The samples were then cooled down to room temperature under N2 flow (40 mL min-1). The nitrided ZrO2-WO3 was designated as mZW-NH3. The mZW-NH3 powder was placed in a crucible and heated in a furnace. The temperature was increased at a ramp rate of 5 ºC min-1 to 550 ºC under static air and maintained for 5 h to obtain mZW-NH3-air product. Characterization methods X-Ray diffraction analysis (XRD) data were recorded on an Ultima IV diffract meter using CuKa radiation with a step size of 0.02º and operated at 3 kW. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms were obtained using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 at 77 K. The samples were pretreated under vacuum at 300 ºC for 3 h prior to N2 adsorption and desorption. The pore size distribution was obtained from desorption branch using the BJH model. X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out on a Thermo Scientific K-alpha spectrometer using Al-Ka X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The pressure inside the analysis was maintained at 5 × 10-7 mbar. The C 1s line at 284.8 eV was used for the correction of binding energies (BE). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging was performed in JEOL 2010 electron microscope operating at 200 kV. The samples were supported on carbon-coated copper grids. Ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-Vis-DRS) was recorded using a Shimadzu spectrometer with BaSO4 as background spectrum, with a scanning step of 0.5 nm. The acid properties of the samples were determined by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), spectra of adsorbed pyridine (Py-IR) and temperature-programmed desorption of ammonia (NH3-TPD). FT-IR experiments were conducted on Tensor 27. The sample was treated at 450 ºC for 1 h under vacuum (1 Pa), cooled down to 150 ºC, and then exposed to pyridine vapors. The excess pyridine was removed by out gassing for 1 h. FT-IR spectra were obtained at room temperature after desorption at 150 ºC. NH3-TPD was recorded on an AutoChem1 II 2920 instrument with a thermal conductivity detector. About 0.10 g fresh sample was pretreated in air at 500 ºC for 1 h, followed by adsorption of NH3/air (10% v/v) at 100 ºC for 1 h, and purged under high purity helium. The NH3-TPD measurement was carried out from 100 to 500 ºC with heating rate of 10 ºC min-1. Acid-catalyzed reaction The F-C reaction of anisole and benzyl alcohol (BA for short) was carried out in a three-necked flask reactor. The reaction system was performed using 0.1 g catalyst, 5.445 mL anisole and 0.518 mL BA in an oil bath at 124 ºC for 1 h. The concentration of each substrate was analyzed by a gas chromatography (GC-2014, Shimadzu) equipped with a capillary column (SE-54 with dimensions of 30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.50 µm), using n-decane as an internal standard. The BA conversion and selectivity were calculated according to reference 21.

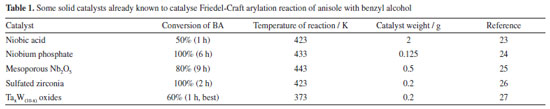

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The structure was characterized using wide-angle powder XRD patterns. It reveals the presence of crystallized zirconium oxide, including tetragonal zirconia (t-ZrO2) with characteristic peaks at 30.1º and 35.1º and monoclinic zirconia (m-ZrO2) with peaks at 28.2º and 31.4º in both materials (Figure 1a). Meanwhile, bulk crystallized tungsten oxide (WO3), which typically exhibits three sharp peaks at 23-25º, is not detected in this pattern, indicating that W was homogeneously dispersed in crystallized zirconium oxide. XRD results indicate that ammonia-air calcination does not impact the crystal structure or tungsten dispersion. N2 Sorption measurement exhibits that the obtained isotherms are of type IV with H2 type hysteresis and confirms that the materials have typical mesoporous networks (Figure 1b). The BET surface area of mZW and mZW-NH3-air was 23.0 and 17.7 m2 g-1 respectively. The pore size distribution of both materials about 3.9 nm (Figure 1c). N2 Sorption characterization indicated that NH3-air calcination did not influence the mesoporous structure of mZW. The signals of mZW-NH3-air in Raman spectra were weak due to strong fluorescence. The W/Zr molar ratios of mZW and mZW-NH3-air samples, as detected by XPS analysis, are 0.236, and 0.245, respectively. The actual surface W density is comparable for both catalysts and exceeds the theoretical value (0.111). This indicates that some W atoms migrated from the bulk to the surface during high-temperature calcination.

Figure 1. (a) XRD patterns; (b) N2 adsorption-desorption curve and (c) pore size distribution (calculated by BJH model) of mZW and mZW-NH3-air

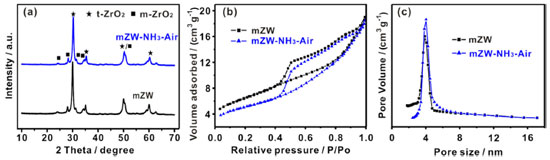

The acid properties of the catalysts were analyzed by pyridine-adsorbed infrared spectroscopy (pyridine-IR). Figure 2a shows the pyridine-IR spectra, which exhibit characteristic bands at 1611 and 1445 cm-1 corresponding to adsorption on Lewis acidic sites (coordinate unsaturated Zr4+ cations), a weak band at 1540 cm-1 due to the formation of pyridinium ions by the interaction of pyridine with Brønsted acid sites, and a peak at 1489 cm-1 representing a combination of pyridine on both Lewis and Brønsted acidic sites.22 Both mZW and mZW-NH3-air catalysts contain Lewis acid sites as well as Brønsted acid sites. The intensity of these bands increased for mZW-NH3-air catalysts after annealing under NH3 and air atmosphere, indicating that the relative amounts of Brønsted and Lewis acidity in mZW-NH3-air are greater than in mZW.

Figure 2. mZW and mZW-NH3-air catalyst. (a) Pyridine-IR spectra (150 ºC), (b) NH3-TPD spectra and (c) the conversion of BA (1 h) in the F-C reaction

The acidity of the catalysts before and after NH3-air calcination was also analyzed using NH3-TPD. The NH3 desorption profile (Figure 2b) in the temperature regions can be classified into two groups: one peak with a maximum at about 200 ºC, and the other peak at 330 ºC, corresponding to "weak" and "medium strong" acid sites, respectively. The NH3-air calcination treatment resulted in a higher desorption temperature of NH3, indicating stronger acidity, and a larger desorption area, inferring an increased amount of acid sites. The F-C reaction of anisole and benzyl alcohol (BA for short) was carried out to further investigate the properties of the acidic sites on catalyst surfaces. The reaction is known to proceed on strong or moderately strong Brønsted acid sites. This reaction activity increases with rising of acid strength and/or acid amount. After the reaction, ortho-benzylanisole, para-benzylanisole and dibenzylether (a by-product) are formed. After 1 h reaction, the conversion of BA on mZW is low, about 5.6% (selectivity is 74.2%), while that of mZW-NH3-air is as high as 70.5% (selectivity is 87.2%), as shown in Figure 2c. The increased amount of Brønsted acid sites on mZW-NH3-air is credited to its enhanced catalytic activity in F-C reaction. mZW-NH3-air shows higher activity in this F-C reaction compared to niobic acid and niobium phosphate and mesoporous Nb oxide catalysts,23-25 and better stability than sulfated zirconia,26 and lower price than NbxW(10-x) oxide and TaxW(10-x) oxide,25,27 as detailed in Table 1. To verify the indispensability of NH3 and air calcination, we employed mZW-NH3 and mZW-air-air (similar to mZW-NH3-air, except for the replacement of NH3 by air) as counterparts. The conversion of BA on mZW-NH3 and mZW-air-air is 0.7 and 18.3%, respectively. The poorer activity of mZW-NH3 was likely due to decline in Brønsted acidity caused by thermal treatment under ammonia, as previously reported.13 The acidic activity was enhanced after being calcined at higher temperature in air. However, the degree of increase the amplification (3.3 times) is not as notable as that achieved by NH3-air sequential calcination (12.6 times). It is suggested that NH3-air subsection-calcination can enhance the acidity and catalytic activity of ZrO2-WO3 solid acid greatly.

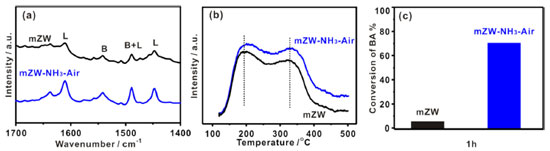

As reported, WOx clusters incorporating some zirconium cations are the most active species in WO3-ZrO2 catalysts.28 We used high-resolution TEM to directly image the various WOx species present in WO3-ZrO2 catalysts. Representative HRTEM images of WO3-ZrO2 materials are shown in Figure 3, which possess clear nanocrystalline ZrO2 lattice fringes on both materials. No darker speckles, ascribed to W atoms, were found at the boundaries or surface of aggregates of ZrO2 particles in mZW catalyst. In contrast, the mZW-NH3-air displayed some dark speckles (marked with white circles) caused by either amorphous interfacial films or clusters on the nanocrystalline ZrO2 support. Based on their corresponding catalytic activities and related literature, we proposed these dark speckles were WOx subnanometer clusters induced by NH3-air subsection-calcination. These results support the notion that NH3-air subsection-calcination is associated with the generation of WOx clusters, which are responsible for the strong Brønsted acidic sites.

Figure 3. Representative TEM images of: (a) mZW and (b) mZW-NH3-air (white circles indicate WOx clusters)

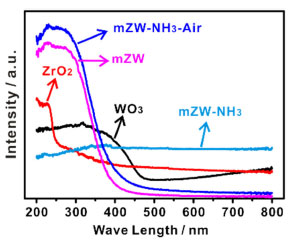

Information on the chemical nature and coordination states of tungsten oxide species was obtained by UV-Vis diffuses reflectance spectroscopy, as shown in Figure 4. The peak at 240 nm is attributed to the edge position of t-ZrO2 phase. Inspection of the spectra clearly shows that the absorption peak of both WO3-ZrO2 materials shifts to longer wavelengths relative to the edge position of pure zirconia due to the presence of W species. The bands at 220 and 260 nm ascribed to tetrahedral W(VI) and octahedral W(VI), respectively.29 The position of the inflection points as determined from first derivative spectra is below the value of 449 nm found for crystalline WO3, suggesting that no bulk WO3 is formed in either WO3-ZrO2 materials. Furthermore, calcination under NH3-air shifts the edge position to a longer wavelength compared with mZW. It has been reported that in the domain size for WO3 range below 10 nm, the band gap energy increases with decreasing domain size.30 Therefore, the up-shift in UV-Vis-DRS spectrums may be attributed to the generation of WO3 clusters. The DR-UV-Vis results, together with HRTEM images, indicate that NH3-air subsection-calcination can induce the formation of WOx clusters as active sites.

Figure 4. The reflectance spectra of mZW and mZW-NH3-air (ZrO2 and WO3 were used as references)

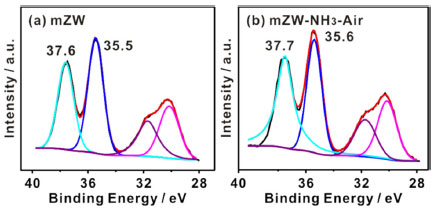

The ammonia would create a reductive atmosphere that generate W5+ ions coexisting with W6+ ions, potentially significantly influencing the acidic properties of WOx and its resulting activity towards F-C reaction.31,32 X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy was used to determine the oxidation state of W in all catalysts. The W atoms were identified as W6+ species with the most intense peak occurring at 35.5 ± 0.1 eV and the lower one at 37.7 ± 0.1 eV (Figure 5).3,6 The NH3-air calcination process did not reduce the W atoms. Instead, it shifted the W4f peaks to a higher binding energy, likely due to the transition from isolated WOx species to polytungstate clusters in mZW sample.33

Figure 5. W4f XPS spectra of (a) mZW and (b) mZW-NH3-air

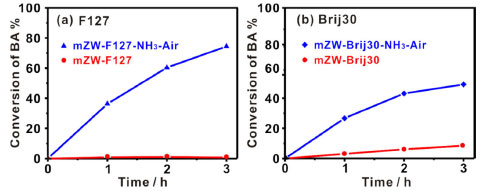

To further validate the effectiveness of the NH3-air subsection- calcination method on activity, we synthesized two additional WO3-ZrO2 materials under different surfactants (mZW-S). Both materials were subjected to NH3 calcination followed by air calcination (denoted as mZW-S-NH3-air). The results of catalysis are shown in Figure 6. The catalytic activity of mZW-S is greatly improved after NH3-air subsection-calcination, in good agreement with previous results. Therefore, it can be concluded that NH3-air subsection-calcination is an effective method for improving the acid catalytic activity of WO3-ZrO2 materials. However, the mechanistic function of WOx clusters induced by NH3-air subsection-calcination treatment is not fully understood.

Figure 6. The BA conversion vs. reaction time in the F-C reaction using mZW-S as catalysts with different surfactant: (a) F127 and (b) brij30

CONCLUSIONS In summary, we have successfully synthesized a variety of acidic WO3-ZrO2 materials using sol-gel method. Their structures and acid properties were thoroughly characterized through XRD, N2 adsorption measurement, Py-IR, NH3-TPD and XPS analysis. In addition, the acidity of ZrO2-WO3 materials can be significantly enhanced through NH3-air subsection-calcined treatment. We identified that the subnanometer WOx clusters act as the most active sites for the F-C reaction evidenced by UV-Vis-DRS and HRTEM characterization. Furthermore, NH3-air calcination is essential for the formation of WOx clusters. Most importantly, the reverse acidification approach utilizing NH3-air subsection-calcination provides a novel strategy for designing acid catalysts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (22002141, 32271528) and China Scholarship Council Fund (202009570002).

REFERENCES 1. Hino, M.; Arata, K.; J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1988, 18, 1259. [Crossref] 2. Hino, M.; Arata, K.; J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1988, 17, 1168. [Crossref] 3. Cortes-Jacome, M. A.; Angeles-Chavez, C.; Lopez-Salinas, E.; Navarrete, J.; Toribio, P.; Toledo, J. A.; Appl. Catal., A 2007, 318, 178. [Crossref] 4. Yamamoto, T.; Orita, A.; Tanaka, T.; X-Ray Spectrom. 2008, 37, 226. [Crossref] 5. Ji, W. J.; Hu, J. Q.; Chen, Y.; Catal. Lett. 1998, 53, 15. [Crossref] 6. Kim, T. Y.; Park, D. S.; Choi, Y.; Baek, J.; Park, J. R.; Yi, J.; J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 10021. [Crossref] 7. Devassy, B. M.; Halligudi, S. B.; J. Catal. 2005, 236, 313. [Crossref] 8. Wong, S. T.; Li, T.; Cheng, S. F.; Lee, J. F.; Mou, C. Y.; J. Catal. 2003, 215, 45. [Crossref] 9. Torres, G. C.; Manuale, D. L.; Benitez, V. M.; Vera, C. R.; Yori, J. C.; Quim. Nova 2012, 35, 748. [Crossref] 10. Rao, Y.; Trudeau, M.; Antonelli, D.; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13996. [Crossref] 11. Soultanidis, N.; Zhou, W.; Psarras, A. C.; Gonzalez, A. J.; Iliopoulou, E. F.; Kiely, C. J.; Wachs, I. E.; Wong, M. S.; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13462. [Crossref] 12. Senso, N.; Jongsomjit, B.; Praserthdam, P.; Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 1537. [Crossref] 13. Lyu, J. H.; Hu, H. L.; Rui, J. Y.; Zhang, Q. F.; Cen, J.; Han, W. W.; Wang, Q. T.; Chen, X. K.; Pan, Z. Y.; Li, X. N.; Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 482. [Crossref] 14. Xia, Y.; Mokaya, R.; J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 1455. [Crossref] 15. Wiame, H.; Cellier, C.; Grange, P.; J. Catal. 2000, 190, 406. [Crossref] 16. Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; J. Mater. Res. 2007, 22, 3330. [Crossref] 17. Narasimharao, K.; Hartmann, M.; Thiel, H. H.; Ernst, S.; Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 90, 377. [Crossref] 18. Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Suo, J.; Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 336. [Crossref] 19. Tagusagawa, C.; Takagaki, A.; Iguchi, A.; Takanabe, K.; Kondo, J. N.; Ebitani, K.; Hayashi, S.; Tatsumi, T.; Domen, K.; Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1128. [Crossref] 20. Li, S.; Jin, C.; Feng, N.; Deng, F.; Xiao, L.; Fan, J.; Catal. Commun. 2019, 123, 54. [Crossref] 21. Li, S.; Yu, R.; Xu, B.; Wang, Z.; Wu, C.; Guo, J.; RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 13406. [Crossref] 22. Sugeng, T.; Takashi, Y.; Hideshi, H.; Appl. Catal., A 2003, 242, 101. [Crossref] 23. Morais, M.; Torres, E. F.; Carmo, L.; Pastura, N.; Gonzalez, W. A.; Santos, A.; Lachter, E. R.; Catal. Today 1996, 28, 17. [Crossref] 24. de La Cruz, M. H. C.; da Silva, J. F. C.; Lachter, E. R.; Catal. Today 2006, 118, 379. [Crossref] 25. Rao, Y. X.; Trudeau, M.; Antonelli, D.; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13996. [Crossref] 26. Miao, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, D.; Bi, X.; Chou, L.; Zhuo, S.; Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 411, 419. [Crossref] 27. Tagusagawa, C.; Takagaki, A.; Iguchi, A.; Takanabe, K.; Kondo, J. N.; Ebitani, K.; Tatsumi, T.; Domen, K.; Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 3072. [Crossref] 28. Zhou, W.; Ross-Medgaarden, E. I.; Knowles, W. V.; Wong, M. S.; Wachs, I. E.; Kiely, C. J.; Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 722. [Crossref] 29. Wang, H.; Guo, Y. G.; Chang, C. R.; Zhu, X. L.; Liu, X.; Han, J. Y.; Ge, Q. F.; Appl. Catal., A 2016, 523, 182. [Crossref] 30. Scheithauer, M.; Grasselli, R. K.; Knozinger, H.; Langmuir 1998, 14, 3019. [Crossref] 31. Li, S.; Zhou, H.; Han, B.; Deng, F.; Liu, X.; Xiao, L.; Fan, J.; Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 719. [Crossref] 32. Barton, D. G.; Soled, S. L.; Meitzner, G. D.; Fuentes, G. A.; Iglesia, E.; J. Catal. 1999, 181, 57. [Crossref] 33. dos Santos, V. C.; Wilson, K.; Lee, A. F.; Nakagaki, S.; Appl. Catal., B 2015, 162, 75. [Crossref] |

On-line version ISSN 1678-7064 Printed version ISSN 0100-4042

Qu�mica Nova

Publica��es da Sociedade Brasileira de Qu�mica

Caixa Postal: 26037

05513-970 S�o Paulo - SP

Tel/Fax: +55.11.3032.2299/+55.11.3814.3602

Free access